Manifest Destiny and the Religious Mechanization of Providence

My Third Research Post for HIS 467

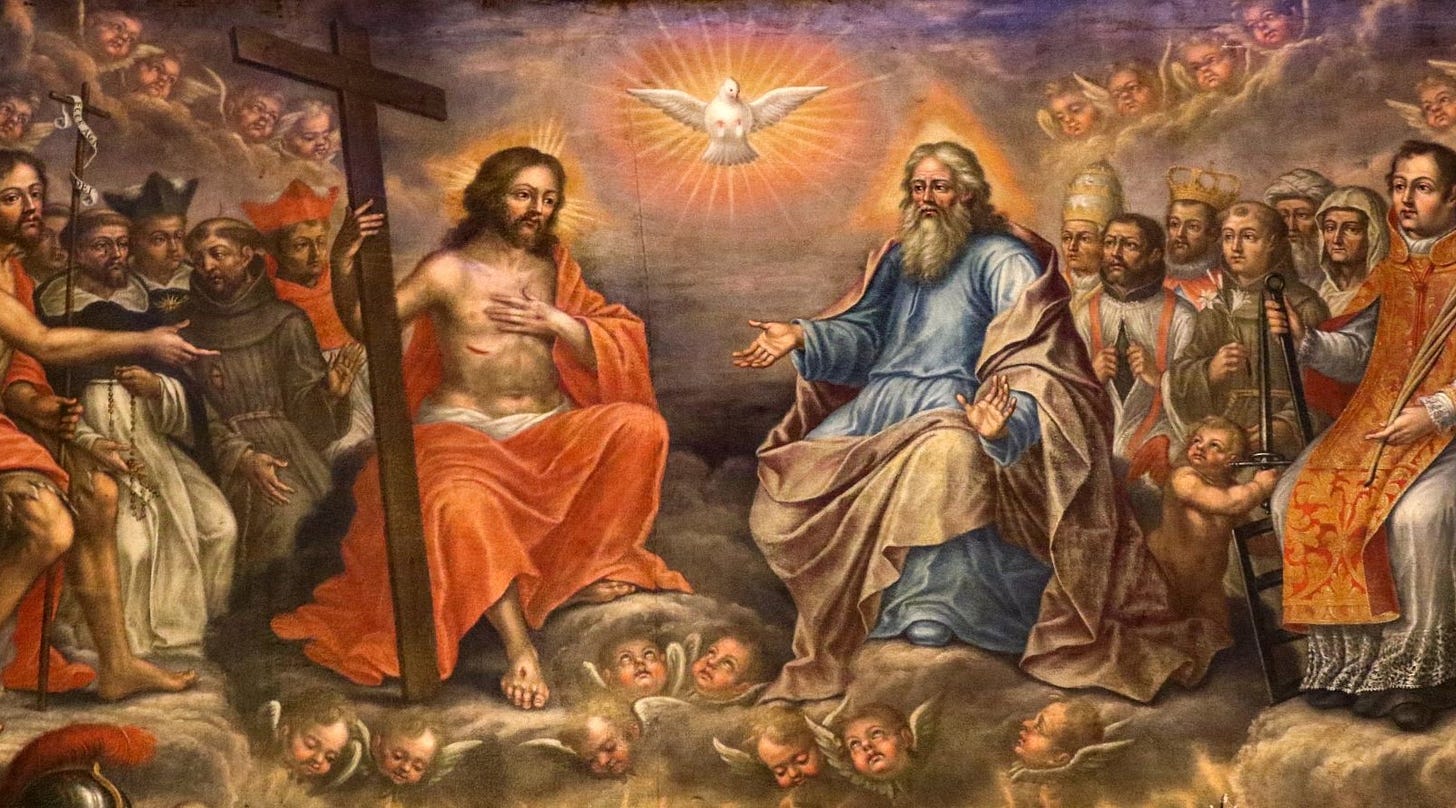

When taught in schools, Manifest Destiny is often taught to be a political doctrine and a geographic ambition, but there are some very deep theological concepts to grapple with here as well. Beneath the lairs of patriotism and nation progress, there is a powerful combination of enlightenment ideals and protestant religious beliefs. This combination of ideologies is what I will refer to as the religious mechanization of providence, or the idea that American settlers mechanized the idea of God’s intervention in their efforts. This mindset not only framed American exploration as an inevitability, but also as a mandate from God. The Mechanistic Worldview, a remnant of the Enlightenment, made out the universe to be a vast and rational system that was governed by fixed laws. Protestant Theology at this time depicted God as a supreme architect who had finely tuned plans for humanity that would unfold as time marched on. When these two ideals merged in the nineteenth century, they glorified westward expansion as both a sacred means of fulfilling God’s plan as well as an inevitable expansion of U.S. power.

Manifest Destiny was a term created by journalist John O’Sullivan in 1845, when he claimed that it was America’s “manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence.”¹ The utilization of the word Providence here is not accidental, but rather a by product of the typical American life in the nineteenth century being steeped in religious culture. The success of a nation, the prosperity of industry, and the spread of Christianity were all measurements used at the time to showcase God’s will. It was a fundamental belief that America was chosen by God to lead the world forward, to spread our culture, our economics, and our religion.

To really capture this worldview, it is important to mention the metaphor of the clockmaker God. Some prominent enlightenment thinkers, such as Isaac Newton, viewed the world as a well constructed machine, created by God to obey his own words.² When Americans encountered this idea, they viewed it as rational and natural rather than chaotic or mysterious. When we apply this idea to Manifest Destiny, it instantly made conquest into duty, a sense of responsibility to carry it out manifested. The violent conquering of the west, the displacement of American Indians and the constructions of urban cities were not just acts of the state, but rather acts in the name of God’s plan.

This vision of Manifest Destiny was also embraced by the political leaders of the time. Presidents ranging from Thomas Jefferson to James K. Polk also view Manifest Destiny as a divine version of God’s plan. The Mexican-American War that occurred under the leadership of James K. Polk in 1846 resulted in the U.S. gaining half of Mexico’s territory. The act of conquest here was justified through the logic that they view Mexican Catholicism as inferior to the American Protestant system.³ The conquest here was thus transformed from conquest to religious truth.

The land in itself was a major target of Manifest Destiny and resulted in the destruction of a lot of nature. A settlers’ farm wasn’t just a system of production, but also a sign from God that they were higher beings. The Indigenous versions of farming were looked down upon because of their lack of integration of more relevant technology, but settlers were looked upon fondly because of their utilization of scientific improvements. This is true with a lot of systems in the west, such as railroads, irrigation systems, and town grids.⁴ In this way, we can view the material infrastructure of Manifest Destiny as products of God’s plan.

Mechanized Providence has had devastating consequences to both peoples and the land. By making the process of conquest sacred, the suffering of the Indigenous people was marked as necessary and erased from the public eye. As scholar Frederick Merk points out, the religious mechanization of providence “rationalized conquest and cloaked it in moral garments”.⁵ The marginalized and suppressed voices of those who suffered at the hands of Manifest Destiny and the Mechanistic Worldview can never truly be accounted for.

In conclusion, Manifest Destiny cannot be fully understood without an in depth look into the process of religious mechanization of providence. The utilization of this mindset allowed for the American conquest of the west to be widely viewed as necessary and not a big deal, when they are a vastly import aspect of the history of the United States and how we marginalized them as well.

John L. O’Sullivan, “Annexation,” The United States Magazine and Democratic Review, July–August 1845.

Isaac Newton, Principia Mathematica, ed. Andrew Motte (1729).

Amy Greenberg, A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico (New York: Knopf, 2012), 29–40.

Leo Marx, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1964), 158–172.

Frederick Merk, Manifest Destiny and Mission in American History (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963), 68.